Campus architecture of the 60s

Blossoming of architecture and art in the Saarland

The 1950s and 1960s were a real heyday for modern architecture and architectural art in the Saarland. This was especially true for the still young, but rapidly growing Saarland University on its way to Europe. The Mensa was also born out of this spirit. Many of these special individual buildings, like the Mensa, are listed as historic monuments.

French cultural policy had a strong influence on urban planning and education as well as art and culture in the French-administered Saar region (1947-1955). The first phase of expansion of Saarland University, which was initially founded as a dependence of the French university in Nancy, under the French rector Joseph-François Angelloz (between 1950 and 1956), with the founding of the Europa-Institut in 1951, at the same time formed the foundation stone for its bi-national and European orientation.

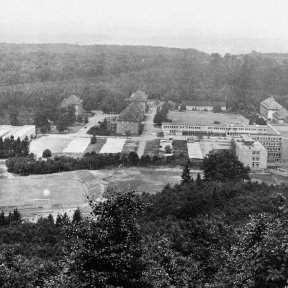

Architect Richard Döcker, who incidentally was Walter Schrempf's teacher, had won an urban planning competition for the Saarbrücken campus in 1952 with an overall design around a forum on the site south of the former Below barracks. High-caliber individual buildings by renowned German and French architects were thus created with the involvement of artists for the design in the Saarbrücken city forest. Many of these are now listed buildings in need of renovation.

Educational and other public buildings from this period were characterized by 'Classic Modernism', which was strongly oriented towards the Bauhaus - functional, reduced, inexpensive, social, democratic and true to form. Skeleton buildings made of reinforced concrete with a cubic, geometric design language and the use of concrete, a versatile building material, characterize these buildings. The library building by architect and urban planner Richard Döcker (1952-1954), the Faculty of Philosophy by André Remondet (1953-1954), the extension of the Faculty of Natural Sciences (1957-1960) and also the refectory (1965-1970), both designed by architect Walter Schrempf, also follow this pattern.

Publisher: Ministry of Environment, Energy and Transport - State Monuments Office. Edition: 2011, price 19,00 EUR, ISBN 978-3-927856-14-1. The book presents 158 objects in the manner of a compendium, which as a selection allow an overview of architecture and urban development in the Saarland of the post-war period. Contents include 'Saarland University' p. 26-27, Auditorium Maximum of the Faculty of Law and Economics p. 28, University Library p. 29, Faculty of Natural Sciences p. 38, Lecture Hall Biological Institutes p. 31, Faculty of Philosophy p. 39, Mensa p.

It is precisely these buildings that have embodied and integrated art in construction in a special way to this day. This is no coincidence. For one thing, at the time, Kunst am Bau was part of the publicly funded construction and educational mandate for public buildings. For another, versatile and in some cases pioneering artists were active at the Werkkunstschule Saarbrücken, which was directed from 1952-1959 by Otto Steinert, the founder of Subjective Photography. Artists such as Wolfram Huschens, Boris Kleint, Herbert Strässer and Max Metz have left their mark on these individual buildings to this day. For example, the architect of the Mensa Walter Schrempf was co-founder of the Deutscher Werbund Saar in 1957/58 and also head of the class for interior design at the Werkkunstschule and very good friends with Professor Robert Sessler (graphic design) and Peter Raake (industrial design).

The Mensa, however, breaks out of the category of 'art in architecture' in that an almost symbiotic unity of architecture and art has been achieved here. Architect and sculptor together created a total work of art in which building and art merge almost invisibly.

Both functionally and sculpturally, the Mensa also draws strong inspiration from the so-called 'Brutalism' (béton brut) modelled on Le Corbusier (1887-1965), a master of the structural and form-giving use of concrete, which was popular as a building material for educational buildings and social housing until the 1980s.

This period of post-war architecture in Saarland, which is probably the most diverse in terms of art and building history as well as construction technology, can be rediscovered until the mid-1970s at the Saarbrücken and Homburg campuses of the university.

Root

Root Description