The Mensa building

Reflections in the historical context

First of all, in order to better understand the Mensa building, it is necessary to dig out a little and explain its architectural and socio-historical context. Laura Weidig explains in her article 'Zurück zu Beton' ('Back to concrete') the political aesthetics and philosophy of Brutalism, the social housing construction with concrete that enabled the relatively fast reconstruction of cities and educational buildings in the post-war period.

Laura Weidig, Article 1 ‚Zurück zu Beton'"Use is the best care," is a credo of historic preservation.Laura Weidig in the article „Zurück zu Beton".

Brutalism, this is a generic term of an architectural style that reached its peak between 1955 and 1979. Le Corbusier, one of the most important architects of the 20th century, coined the term béton brut, literally "exposed concrete". The then innovative building material became the central material and design element of his numerous buildings and of an entire generation of architects from the 1950s to the 1980s. Mies van der Rohe also had a decisive influence on Brutalism with the clear, modular structure of the Bauhaus style. Architect Walter Schrempf was inspired by these two giants of modern architecture in his design of the Saarbrücken Mensa, a modularly constructed cube measuring 60 x 60 meters.

Brutalism can confidently be called the most controversial architectural style of the 20th century - at least retrospectively: building sin or great architecture? Is that one of the reasons why it polarizes so much - then as now? Brutalism is a style that doesn't sugarcoat anything. The favorite material is the eponymous, raw concrete, which shows clear traces of the work processes. This raw construction aesthetic immediately jumps out at the sight of brutalist architecture. Building materials are used raw and unprocessed, nothing is disguised, plastered or hidden - "form follows function". Brutalist architects were influenced by the idea of sincerity - buildings and materials should look like what they were, constructions should be 'readable': girders, beams, supply lines - everything must be laid open, remain visible, nothing must disappear behind plaster. At first glance, the viewer should be able to see how the building 'works'. At the same time, this disclosure of the construction celebrated the perfection of craftsmanship: the traces left behind by the construction workers are ennobled in the brutalist architecture as a means of design.

In the overall impression, the buildings look like monumental concrete colossi due to their size, imposing, dramatic, but also interesting from close up because of the surface structure of the concrete.

On the other hand, daily maintenance and upkeep of the 50-year-old building, which has been a listed building since 1997, are a financial and organizational balancing act for the operator of the Mensa, Studierendenwerk Saarland. This is because the Mensa is in urgent need of fundamental and sustainable renovation - the concrete is crumbling, the supply lines are over 50 years old, the roof is leaking, and annual energy and operating costs are high due to a lack of insulation. This will get worse this year and in the years to come due to rising energy prices. The student brochure also draws attention to these grievances and, together with the university-sponsored overall project 'Denk_mal anders - 50 Jahre BauKunst Mensa', supports the sustainable renovation of the building. Energy-efficient renovation proposals are currently in preparation.

On the other hand, daily maintenance and upkeep of the 50-year-old building, which has been a listed building since 1997, are a financial and organizational balancing act for the operator of the Mensa, Studierendenwerk Saarland. This is because the Mensa is in urgent need of fundamental and sustainable renovation - the concrete is crumbling, the supply lines are over 50 years old, the roof is leaking, and annual energy and operating costs are high due to a lack of insulation. This will get worse this year and in the years to come due to rising energy prices. The student brochure also draws attention to these grievances and, together with the university-sponsored overall project 'Denk_mal anders - 50 Jahre BauKunst Mensa', supports the sustainable renovation of the building. Energy-efficient renovation proposals are currently in preparation.

The Mensa is operated and driven by the Saarland Student Union. It is the great constant in the daily hustle and bustle and makes sure that everything in the building works. In particular, it takes care of the basic needs of students - food, housing, welfare, childcare and also support for financing their studies. The administrative offices of the Studierendenwerk are located in the basement of the Mensa. Corinna Kern's article looks at the Studierendenwerk's areas of responsibility from an internal perspective.

Artikel 8 – Das Studierendenwerk von Corinna KernBut the use of the building, which is over 50 years old, currently poses major challenges. It is true that the 'Studentenhaus', as a total work of art outside and inside, is a listed building and has been due to be restored by the state government for several years. But still nothing has happened and so the Studierendenwerk - until recently still an association as 'Studentenwerk im Saarland e.V.' - had to intervene itself to be able to keep the operation of the Mensa running.

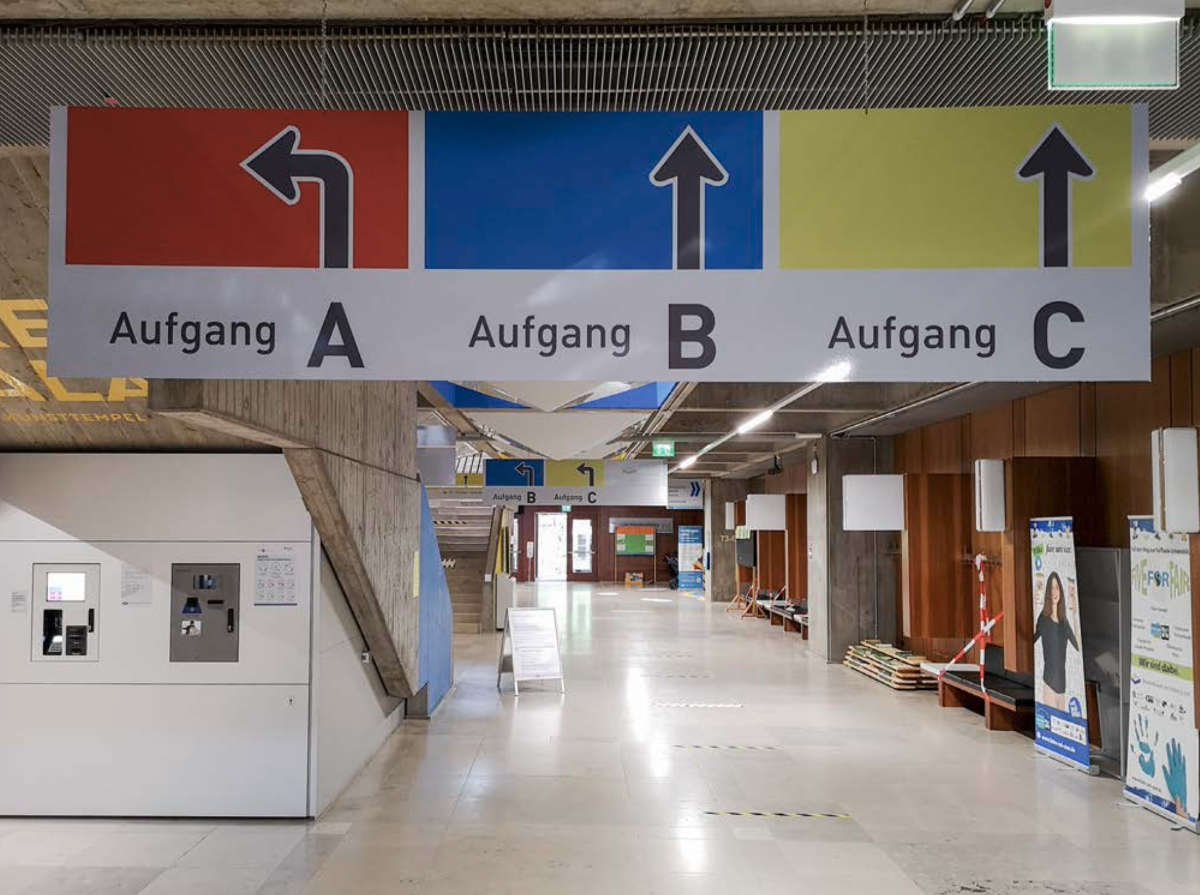

Emergency lighting in the foyer

Emergency measures taken by the Studierendenwerk Saarland include scaffolding around the entire building to catch falling pieces of concrete and emergency lighting in the foyer. The colorfulness of sculptures and facade pieces by sculptor Otto Herbert Hajek on the exterior have also faded. Other costly defects in the building include decaying window frames and seals, as well as single glazing and the lack of thermal insulation, which result in high energy costs each year and place a heavy burden on the Student Union's coffers. Other energy costs necessary for operations are also high. Now, since the COVID pandemic, there is also less revenue.

The Studierendenwerk currently finds itself in a dilemma between usability, preservation and monument protection. In order to better understand the tasks of monument protection in general, Sarah Clement found out what the legal situation in Saarland provides for this. Tabea Motika deals with the concrete situation ‚Zwischen Denkmalschutz und Nutzbarkeit‘ ('Between monument protection and usability' ) on site in the Mensa.

Article 2 ‚Einfach Denkmalschutz‘ by Sarah Clement Article 3 ‚Denkmalschutz versus Nutzbarkeit?‘ by Tabea Motika